DAILY DOSE of BEETHOVEN (October 14, 2020)

In 1811, Beethoven was commissioned to compose incidental music for two new plays by August von Kotzebue, entitled "The Ruins of Athens", and "King Stephen: or Hungary's First Benefactor." While these works represent neither the composer nor playwright at their best, there's more to them than meets the ear, and they do not deserve the obscurity to which they have been relegated.

HISTORICAL BACKDROP

The two plays were patriotic works of a sort, but were written in a difficult time, when the Napoleonic Wars had been raging for nearly a decade, and Austria twice defeated by Napoleon. The second defeat in 1809, saw the rise of Count (later Prince) Metternich, who, although he emerged later as an opponent of the French Empire; began his career as an advocate of collaboration with them!

Beethoven was an opponent of such collaboration. In 1806, he broke relations with his patron Prince Lichnowsky, after the Prince tried to trick him into playing his music for French officers. Beethoven went home and smashed the bust the Prince had given him of himself, and made the famous pronouncement: "Prince: You are what you are by accident of birth. I am what I am, because of what I made myself to be. There have been, and will be, a thousand Princes. There is only one Beethoven."

The issue for Beethoven was not a problem with the French (he had many admirers amongst them, and often wrote in French), but with accepting military occupation. He simply could not compromise on moral issues. In his declining years, Prince Lichnowsky would climb the stairs to Beethoven's apartment, and listen outside to the playing of the young genius, who he had earlier promoted.

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

At the time, a playwright could not openly protest against occupation by the French Empire. So, in his "Ruins of Athens", Kotzebue may have been using an earlier fight - that of Austria against the Turkish Ottoman Empire, and the liberation of Hungary from that empire - as a metaphor for the more serious situation in his own time.

The Ottoman Empire posed a serious threat, when, in 1683, they came close to conquering Austria. By 1699, Austria won, and had liberated Hungary, which had been decimated, first by a 13th century Mongol invasion, and three centuries later, by a partial occupation by the Ottomans, who saw themselves as descendants of the Mongols.

The Ottoman Empire is reputed to have invented the marching band, designed to strike terror into the hearts of invaded cities, as the fearsome Janissaries (largely abducted Western children, indoctrinated as soldiers of Islam), paraded by. Imagine seeing children you have known, out to kill you. This modern recreation of such an Ottoman Turkish march captures that level of intimidation, especially after 01:10 as it becomes a brutal charge:

https://youtu.be/O-0XDuUfEn0?list=RDRtcTioy0MCU

Historian David Shavin, demonstrated that in 1783, the centennial of that battle, panic swept Austria, and war preparations were being made, out of fear of a new invasion. The Ottoman Empire was however weakened by then, and Mozart helped defuse the war drive with his parody of the feared Turkish marching band. Is this scary?

Study the past, but don't live there! Building the future requires forgiveness, and redemption.

Mozart went further in defusing the war scare, by humanizing the supposed enemy. In his opera, the “Abduction from the Seraglio”, he surprises us by having the Turkish Pasha emerge as the most moral character in the opera.

Beethoven followed Mozart's lead in his Turkish March from "The Ruins of Athens." You can hear the benign marching band approach, pass by, and then fade into the distance:

“The Ruins of Athens” tells a tale of how the Greek Goddess of wisdom and of war, Athena, after sleeping for 2,000 years, awakes to find Athens occupied by the Ottoman Empire, and the Parthenon, which was named after her (from the Greek Parthenos or virgin) in ruins. She then finds Greek virtue and values, in the Hungaian city of Pest.

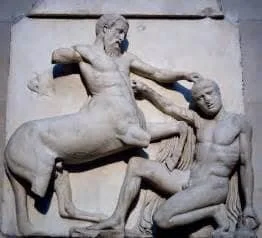

The first part is true. Although the Ottoman Empire no longer posed a serious threat to Western Europe, they continued to occupy Greece until 1824. From 1801-1812, Britain's Lord Elgin carted off the marble statues and friezes of the Parthenon to the British Museum, where they remain today, claiming the occupying Ottomans had authorized him to do so. Neither the Turkish nor Greek governments have ever been able to find any evidence to that effect, and it is today largely believed that Elgin fabricated the authorization.

The part about finding Greek values in Hungary is a bit of a stretch though. The plays were commissioned for the dedication of a new Hungarian Theater in the city of Pest (which later merged with Buda, across the Danube River). The theater's patron was Emperor Franz II. The plays were even performed on the Emperor's Name Day in 1812.

The basic argument of Austria, was that the Holy Roman Empire had liberated Hungary from the Ottoman Empire, and thus brought civilization to it. It was certainly true that Hungary had been decimated by the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, losing as much as 70% of its population, and that central Hungary came under direct Ottoman rule from 1541-1699. Whether it represented a new Athens, is debatable, to say the least.

The "Ruins of Athens" was first performed in 1812, and was revived ten years later for the dedication of a new theater in Vienna. Beethoven composed a new overture for the play, which is today known as "The Consecration of the House."

Here is the original overture from 1811-12, Op. 113:

Here is the 1822 version, Op. 124. Beethoven's progress is evident. It shows evidence of his increased study of Bach and Handel. One can even hear a hint of the double-fugue from the first movement of his Ninth Symphony in it:

Parthenon marbles in the British Museum

Photos by Fred Haight: