Greetings!

On this, Ludwig van Beethoven’s 251st birthday, we continue our celebration and discovery of the great Master and his music-beginning with a six-part series entitled “Musical Masters in Dialogue”—which focuses on a single work: “Symphony No. 4 in E minor” of Johannes Brahms.

What? How, you may well ask, do we celebrate and refine our comprehension of Beethoven, by studying a work of Brahms? It requires many things, including an understanding of the dialogue between musical masters, and a challenge to the false division between Natural Sciences (Naturwissenschaft) and Art (Geisteswissenschaft), which was implemented through the Romantic movement of late 19th century.

According to this doctrine, the “Natural Sciences” consist of the study of objective nature, such as geometry and physics, outside of man, by a cold and calculating scientific method, that operates without emotion or creativity, both of which would stand in the way of said objectivity. Works of Art, however, were deemed to be creative, and passionate. They reflected the subjective inner life of humanity, and were often created impetuously, without being weighed down by thought or deliberation, both of which would stand in the way of said creativity.

Thus, we have, according to Romantic doctrine, either thinking without feeling, or feeling without thinking. Can such an artificial state of affairs actually exist? Could any great art have come into existence in such a world? Could any scientific discoveries have been made thus?

THE SPIRIT OF SCIENTIFIC DIALOGUE

There has long existed among great scientists, a spirit of collaboration in solving problems, and in happily passing some aspects of such problems on to future generations.

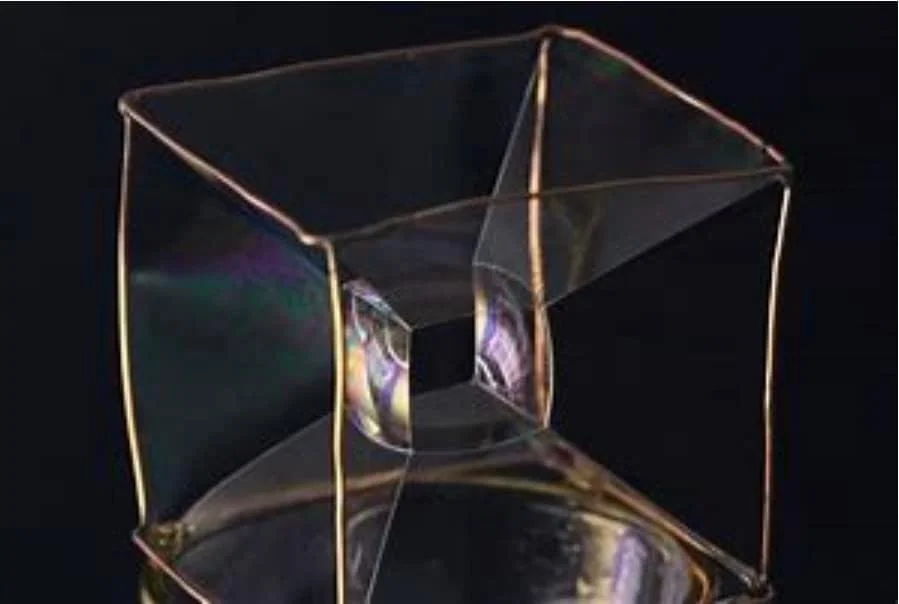

One such set of problems is characterized by what Leibniz called the “Principle of Least Action” (essentially, that nature will always follow the most efficient course). Contributions had been made earlier, including Fermat’s discovery that light will always take during the path of least time (this diagram, accounts for refraction of light according to least time).

1. Fermat Light -least time

The Principle of Least Action. Light will always follow the path of least time. Point P depicts a change in medium, say from air to water.

After Bernoulli issued a friendly challenge to solve the Brachistochrone problem (curve of least time), several responses were received, and these types of investigation, which had been carried forward from Fermat and others, extended into the future as well. Though scientific discovery is a good in itself, it usually led to the benefit of mankind.

2. Tautochrone ( all of the balls will reach the bottom at the same time.)

The time taken by an object sliding without friction in uniform gravity to its lowest point along the curve is independent of its starting point.

3. Brachistochrone curve (the curve of least time.)

In 1696, Johann Bernoulli issued the following friendly challenge to solve the Brachistochrone (least time) problem.

“I, Johann Bernoulli, address the most brilliant mathematicians in the world. Nothing is more attractive to intelligent people than an honest, challenging problem, whose possible solution will bestow fame and remain as a lasting monument. Following the example set by Pascal, Fermat, etc., I hope to gain the gratitude of the whole scientific community by placing before the finest mathematicians of our time a problem which will test their methods and the strength of their intellect. If someone communicates to me the solution of the proposed problem, I shall publicly declare him worthy of praise.”

THE SPIRIT OF MUSICAL DIALOGUE

Could such a dialogue exist in art, in music? Could an investigation into the Principle of Least Action take place there? The aforementioned Romantic doctrine would seem to say no. An artist has deep-seated emotions, and must undergo a strong catharsis in order to express them, to “get them out.” Such a view suggests a purely internal, and timeless origin for a creative work of art. It tends towards the idea of “Art for Art’s Sake”. Let Art speak for itself they say. It has no need of analysis, and need not justify its existence, nor benefit mankind.

Let us remember that this Romantic doctrine is fairly new. Though it has historical precedents, the deep connection between science and art used to be much better understood. Sometimes composers quote each other as a sign of respect. At others times, the quote is much deeper. They are quoting an essential discovery, and how to carry it much further, including with artists they never met.

Although Mozart was familiar with Bach’s sons, he first encountered J.S. Bach in 1782 at the salon of Baron von Swieten. Old Bach’s music was considered elitist, and too complex for ordinary people, so it was seldom played. Mozart took up the challenge. He began composing fugues, and incorporating other challenges from Bach into his music. Why? There are great difficulties involved. Mozart must have sensed that rather than being too complex, Bach’s counterpoint could elevate people to a higher level than the then popular melody and simple accompaniment.

Mozart responded in such a way to Bach’s “Musical Offering”, first with a fugue,K426, in 1783,

then the next year with his his Piano sonata in C minor, K457. But then, he carried it much further in his Fantasy in C minor, K475.

Here is “The King’s Theme” from Bach: next, the opening of Mozart’s Fantasy. (See photo sample)

4. Musical Offering King's Theme (today we discuss just the first five notes.) Noted 4 and 5 (Ab and B) from the diminished 7th interval, which implies the Lydian intervals.

5. Mozart Fantasy First 7 notes

The notes are identical to the first five notes of Bach's Musical Offering, except for the repetition of C, and the crucial addition of F#.

The crucial addition in the Mozart is the tone F#. Many productive hours may be spent, and have been spent (including by this author), in elaborating these works. However, we find it best to concentrate on the fundamentals before advancing. Sometimes the most elementary discoveries, are also the most profound.

Beethoven elevated this dialogue to a sublime level in his final Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111. Bach had featured in his “Musical Offering” the large and dissonant interval—the diminished 7th—in the melody. That interval also implies what are sometimes termed Lydian intervals (tritones).

Beethoven, in the introduction to his Op. 111, abandoned melody, theme and key. There is no theme! There is no key! Is he lost in ambiguity then? No! It is a precise investigation. He decided that rather than examine Bach’s diminished 7th interval as part of a theme, and build up from there, he would open with it, outside of key or theme, as the beginning of an inquiry into the Well-Tempered System as an entirety.

6. Op. 111 Opening

It opens with the diminished 7th interval, Eb-F#, the interval which both Bach and Mozart highlighted

When Beethoven finally arrives at a theme, it truncates both Bach’s “King’s Theme” (Musical Offering) and the opening of Mozart’s “Fantasy in C minor”, so that they are a one in our minds.

7. Op. 111 Main Theme

The first three notes, C, Eb, and B, truncate both the King's Theme and Mozart's thus invoking them both. The diminished 7th interval is reversed, going from B to Ab.

Later, in a sublime movement, Beethoven recalls the entire opening of Mozart’s Fantasy.

Stay tuned for Part 2.