Johannes Brahms’ “Symphony No. 4, 1st Movement”

The classically oriented successors to Beethoven faced a daunting task. They were committed to maintaining his tradition, but how could one match him, let alone advance over him?

Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Chopin all understood that the first step in continuing this great tradition required that Beethoven's music be anchored in the work of J.S. Bach.

BRAHMS’ EXTRAORDINARY SENSE OF MISSION

For the then young Johannes Brahms, Bach and Beethoven were seminal figures. A portrait of Beethoven guided him at the piano, and one of Bach guarded him over his bed. However, his own vast collection of musical scores included the complete works of Couperin, which he edited; Madrigals by Luca Marenzio; and many other Renaissance works. Brahms recognized that Bach did not come out of nowhere. There is a history of musical discovery leading up to Bach’s great works, and many of Brahms' own compositions were informed by what he learned from Renaissance music.

Something precious, and internal, was driving him to accept his role as the guardian of classical music, against what he saw as dangerous tendencies towards arbitrariness and caprice.

One of the least recognized events in history is the “Manifesto” of 1860. At the time, an effort was made to proclaim that the "Music of the Future'' of Liszt, Wagner et al, was a 'fait accompli'. Historians agree that, in opposition, Brahms led the effort to gather signatories for the “Manifesto”, which counters that idea, saying:

“The undersigned have long followed with regret the pursuits of a certain party, whose organ is Brendel's "Zeitschrift für Musik". The above journal continually spreads the view that musicians of more serious endeavor are fundamentally in accord with the tendencies it represents, that they recognize in the compositions of the leaders of this group works of artistic value, and that altogether, and especially in northern Germany, the contentions for and against the so-called ‘Music of the Future’ are concluded, and the dispute settled in its favor. To protest against such misinterpretation of facts is regarded as their duty by the undersigned, and they declare that, so far at least as they are concerned, the principles stated by Brendel's journal are not recognized, and that they regard the productions of the leaders and pupils of t he so-called New German School, which in part simply reinforce these principles in practice and in part again enforce new and unheard-of theories, as contrary to the innermost spirit of music, strongly to be deplored and condemned.”

There were at least twenty signatories lined up for the Manifesto. But that was sabotaged when it was leaked prematurely to the press with only three signatures, making it seem vindictive. From then on, the battle took place in music and in the concert halls. That battle was far more intense than we sense today.

Sometimes, a dialogue between masters is born out of necessity. No matter what the attitude to the Romantic composers is today, Brahms saw a great danger of increasing lack of rigor in the works of Liszt (whose works he labeled as "swindles"), and those of Bruckner (which he described as "symphonic boa constrictors"). This was not petty jealousy on Brahms' part. He took music far too seriously for that.

Brahms began work on this fourth symphony in 1884. He chose Beethoven and Bach as bookends for the first and last movements. It was a clear demonstration of classical rigor, as opposed to romantic wandering.

The first movement is a masterpiece of the “Principle of Least Action”—which is known in music as “motivfuhrung”—creating an entire movement out of a small group of notes known as a “motiv”. Brahms illustrated the nature of such motives.

What is the smallest unit in music—a note? An isolated tone tells you nothing. Does the single tone C establish C major? Play F after it, and you will hear otherwise. The smallest unit is a unit of action—of motion, an interval.

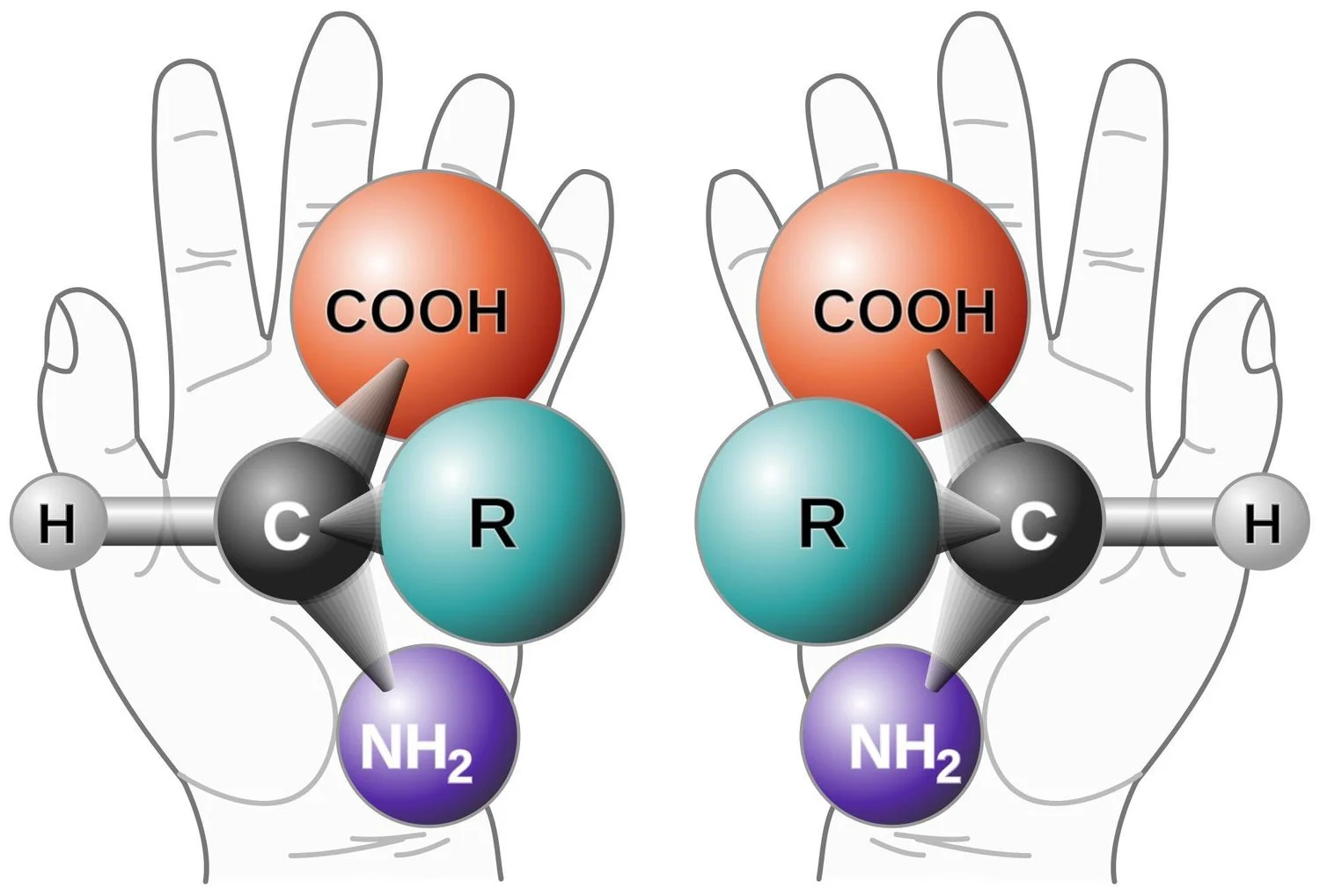

Intervals open up a new and higher level of ambiguity. One of the strongest principles in musical discovery is “inversion”—as it is in the so-called "hard sciences." For example, mirror images in stereochemistry are known as 'chirality' (see example 1)—is the left and right-handed versions of the same molecule. They function differently. Musical intervals can also appear as mirror images. (See example 2).

Chirality: Mirror images in chemistry

Mirror images in music

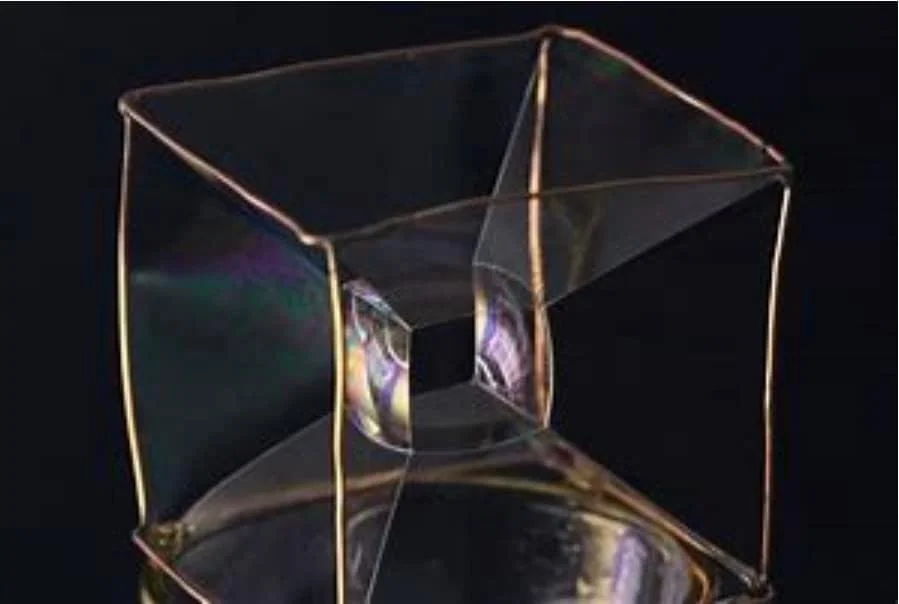

Human creativity has a "pre-established harmony" with the laws of the universe, which will always follow the most efficient pathway. Try dipping a wire cube into the fluid you would use in making soap bubbles. You might expect the soap film to simply cover all six surfaces of the cube. It actually forms a smaller cube inside. Though it looks more complex, it is the minimal surface that the soap film can form. (See example 4)

Least action in soap bubbles

TEXT to Accompany the Audio Description (see below)

Brahms had been in a dialogue with Beethoven's “Hammerklavier”—Piano Sonata No. 29, Op. 106, for all of his life. His Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1, written in Hamburg in 1853, starts with a bold quote from the “Hammerklavier.” The first movement of his 4th Symphony is a response to a section of the slow movement in Beethoven’s Op. 106, in which Beethoven abandons the key signature, and concentrates on the essential movement.

Brahms begins with a simple descending interval in quarter notes—B to G—a major third. He follows with an inversion, an ascending minor 6th—E to C. Then, he moves the entire process down a scale step—A to F#, and D# to B. The entire opening theme looks like this. (See example 3).

Opening Theme of Brahms' 4th Symphony

Anyone who hears this opening will likely comment that it constitutes a "bare-bones " statement, a minimal one. Brahms is demonstrating "freedom necessity." True freedom doesn't come from the license to do whatever you please. Accepting the restrictions of physical reality (including humanity's need for great art), demands more creativity, and leads to more profound discoveries.

How does one make an entire movement out of this? It is not a linear, mechanistic process—not a Lego set. If you try to find the genesis of the movement in linear extensions of the theme, it won't work, and it will be boring. As you can see with the soap bubble, the process of construction according to the “Principle of Least Action” is not linear, but creative.

What? Nature shows creativity?

The second theme, in B minor, might seem unrelated. It is not! The main theme, like the opening, contrasts alternating inversions, in this case the minor seventh and major second. The bass line for that second theme, when put through a series of elementary transformations (mostly octave transpositions), reveals its derivation from the main theme (as illustrated in the audio.)

Brahms continued his experimentation with these transformations well beyond the symphony (as demonstrated in the audio).

Audio: https://drive.google.com/.../1eIj4L1HLDyPSuqe9DF2.../view...

Here is a performance of Brahms’ first moment: https://youtu.be/4uw0l00vb7Q