DAILY DOSE OF BEETHOVEN (September 15, 2020)

Variations: The Three B's

Brahms’ Handel Variations Part 4–the Fugue

For our Grand Finale on Brahms' Handel Variations, we will compare the great fugues at the end of both the Beethoven and the Brahms.

Why study the fugue? When Mozart studied Bach and Handel at the salon of Baron van Swieten in 1782, the fugue was already considered an outmoded form. What did Mozart see in it that would later be affirmed by Beethoven and Brahms? Could it be the way that the fugal form captured both physical reality and creative thought processes, as a unity?

For those familiar with fugues, please indulge us while we introduce the elements of the form. A “fugue” is not a solo with accompaniment. It is a social process, where the idea of the whole, as a process of change, governs; yet that whole could not exist without the unique strength and character of each individual voice, and the evolution each voice undergoes.

In a fugue, one voice begins by itself, with a theme, usually stated in the tonic. So, if we are in C major, the theme will be in C. That voice corresponds to a human voice species, i.e. alto.

When a second voice enters a bit later, it will repeat the theme, but transposed, usually to the dominant. So, if the theme started on C, the answer will begin on the fifth of the scale, G. However, the second voice asks whether that answer takes place in the soprano or tenor voice, depending on whether that G is below or above the opening C.

While the second voice is playing the theme, the first voice proceeds to something else, called the “counter-subject”. It is sometimes new, but often derived from the subject. It usually accompanies the subject throughout the fugue. The standard number of voices in a fugue is four, but it ranges from 2 to 6.

A double-fugue occurs when, instead of a subject and a counter-subject, two fugal subjects of more or less equal weight are developed at the same time, as a pair. As in a good marriage, they are equal, and must undergo a change that is not determined by their individual wills alone, but by the dynamic of the duo.

Fugues often undergo transformations such as inversion, diminution, augmentation, and retrograde. These terms can be understood as geometrical transformations, which have been around since the Renaissance. They're not done for their own sake, as a show of skill, but to facilitate the transformation of an IDEA.

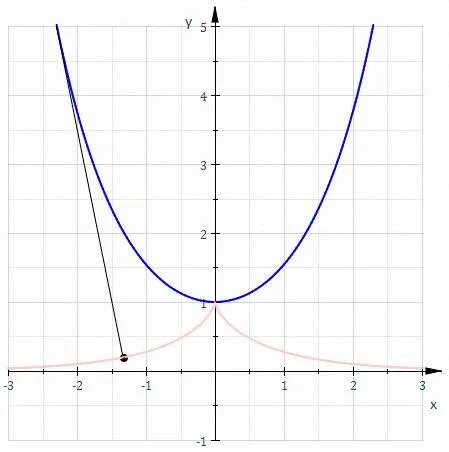

Inversion means upside down, like a mirror image, so a theme that proceeds as C D E, can now go C B A, or C Bb Ab. In geometry, the concept of inversion--of involute and evolute—is not just turning something upside down; it has important physical implications (see photo below of the involute of catenary). What does inversion mean in thought? Suppose you rehearse for hours an enraged response to an injustice and the many ways it might play out. Then, you invert the problem: What if you decide to let it pass? In His “Sermon on the Mount”, Jesus Christ says he is not out to overthrow the law, but to fulfill it. That only makes sense with the concept of “inversion”. Invert “an eye for an eye" onto "turn the other Cheek."

Diminution means shortening the note values, so that a theme that took four measures in quarter notes will now take two measures in eighth notes. Thus, it will sound faster. Diminution could also mean: "I have dwelt too long on this grudge. Let me reduce it, and put it in perspective."

Augmentation is the opposite. The quarter notes are now half-notes, and fill eight measures. Or, augmentation could mean: "I brush over this thought too quickly. Let me draw out its implications."

There is no limit to what we can gain from the study of fugue. We may study a fugue in depth, or delight in the development of ideas as they pass. The very name “fuga” means to flee, and indeed the various voices are fleeting. Before you can fixate on one, the next has arrived. Yet, like rigorous thought, you end up with something definite and concrete.

Today, we include recordings of both Beethoven's and Brahms’ fugues, including a short audio we have prepared to help make these transformations clear.

Here is the audio guide: https://drive.google.com/…/1IszUpzhByjMMoSi3M22hcR_9J-…/view

BEETHOVEN’S DIABELLI VARIATIONS FUGUE:

Here is a recording of the fugue from Diabelli Variations: https://youtu.be/FXjF6Okld4g

Variation 32 begins as a double-fugue. Subject One starts with an Eb to Bb drop of a fourth—an inversion of "motive C" with a rising fourth, G to C. (See photo 2 below—Diabelli theme). The Bb repeats nine times, recalling the repetitive chords of "Motive B". Subject Two features a series of rising half-tones, E F, D Eb, C Db, which recall the inversion of "Motive E" (EF A, F#G B, G#A etc.).

The first fugue subject is in the mid-range of the soprano voice, and the second fugue subject starts out on a tenor high G. This double-fugue starts out as a soprano-tenor duet, with the tenor in full voice.

Theme one is played in inversion at 0:58 in this recording, and themes one and three in diminution at 1:48.

We do not include the final variation, the Minuet, which is worthy of a separate study.

BRAHMS’ HANDEL VARIATIONS FUGUE

Brahms' Handel Variations fugue comes after a huge buildup starting with variation 23. This video includes variations 23, 24, and 25 up to the point of entry of the fugue: https://youtu.be/KQkcDzZ80rU

at Variation 25, the work could be considered successfully concluded. But then, this gigantic fugue ensues!

The fugal subject begins by outlining the first four steps of the Bb major scale—Bb C D Eb, as does the Aria by Handel which provides the basis for the entire set of variations. Fugues usually correspond to human voice types. In the case of this fugue in four voices, it corresponds to soprano, alto, tenor, and bass, although not necessarily in that order (see photo 3–highlighting vocal types).

Brahms starts with the alto voice. Two measures later, at 00:05 the soprano voice enters. Two measures later, at 00:11, the bass voice enters, and two measures later, the tenor. Like all great composers, Brahms makes the stems for bass and tenor voices face down, and sopranos and tenors face up, so the voice-leading will be clear. Like Bach, Brahms is meticulous about using rests to indicate a silent voice. Not only do you know that you are in a four-voiced fugue, you know what the voices are, and where they are. Unlike today, pianos of Brahms' times had different tonal qualities for the different registers. The fugue subject when played in the bass voice, will have a different sound than when played in the soprano.

After this, Brahms introduces something almost imperceptible and seemingly innocuous—the repetition of the dominant tone F, beginning at 00:33 in this recording. Later, towards the end, it will dominate. Is it an arbitrary interjection? Does it come out of nowhere? Just listen to the bass voice in variation 8, which consists almost entirely of Bb and F! It does not come out of nowhere.

With Brahms, geometrical transformations never feel like they are being done for their own sake. Sometimes you don't even notice the technical side. For example, a lyrical and well-prepared inversion of the fugue subject emerges naturally at 1:30 in this recording. It changes the tone! Soon after, the first four notes of the theme and its inversion, enter into a dialogue,

At 2:15 we hear a powerful augmentation of the right-side-up theme in the bass, as if to remind us of where these transformations came from, of where we started.

The climax builds as Brahms reintroduces that repeated F heard at 00:33, and turns it into a powerful octave at 3:50, which then becomes a dominant pedal point in the bass at 04:05, leading to a glorious conclusion.