DAILY DOSE OF BEETHOVEN (September 2, 2020)

The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, was first published in 1741. Consisted of 30 variations, through this work, Bach pushed both keyboard and contrapuntal technique to its limits. Every third variation is a canon at a different interval. (We have colored the first few measures of some of them to help the listener.)

Variation 3 (see picture below) is a canon at the unison. The green is the original voice, and the pink, starting a measure later, is its exact repetition on the same notes.

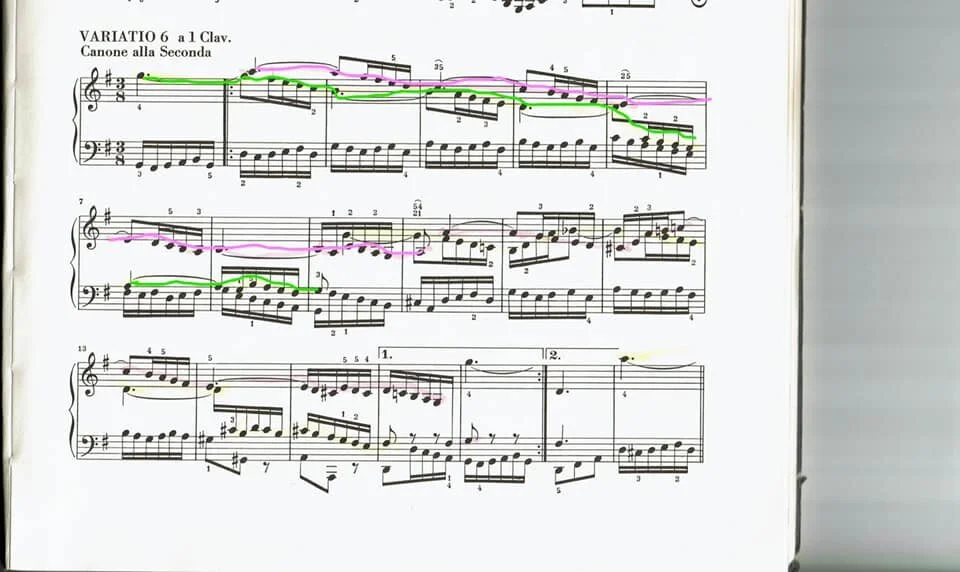

Variation 6 (see picture below) is a canon on the second. The green is again the original voice, starting on G, but the pink starting a measure later, begins on the note A, which is above G by the interval of a second. It remains strictly a canonic imitation of the opening voice, but always a second higher.

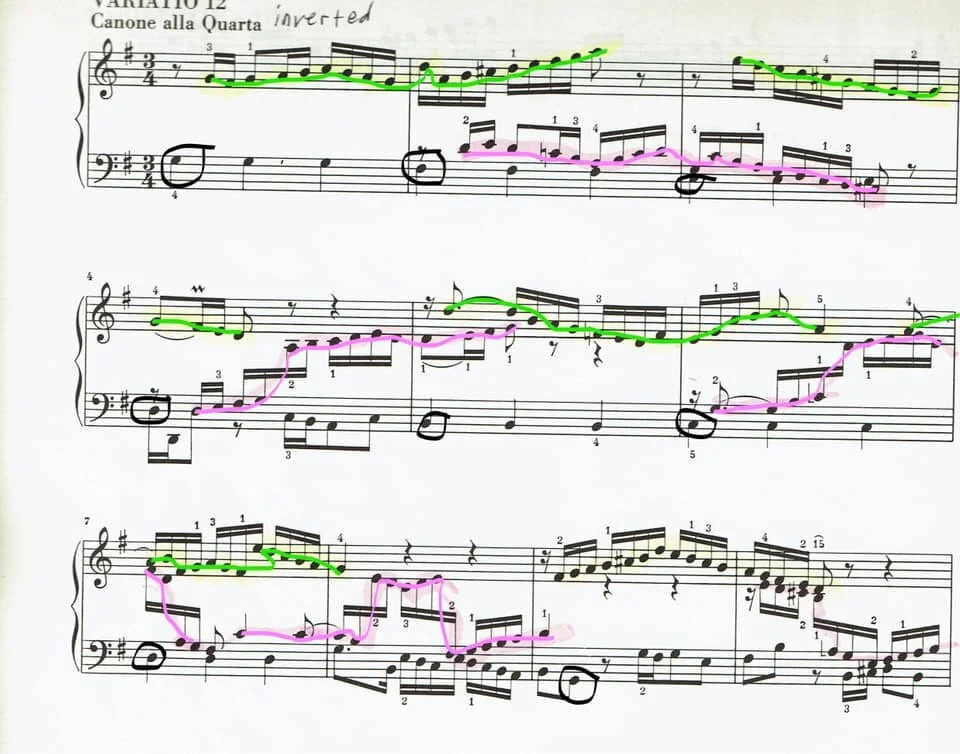

Variation 9 is at the interval of a third, and variation 12 (see picture below) a fourth, but it is inverted. Look closely and you will see that the pink voice begins on D, a fourth below the G of the green voice, but goes in the opposite direction, like a mirror image.

The process continues, with other changes, including the canon at the sixth starting the answering voice half-way through the first measure.

THE BASS LINE

Notice that in two of these diagrams, we have circled 8 bass notes. That bass line—G F# E D B C D G—opens the aria and each variation, although it is sometimes a bit disguised. Bach also decided to compose 14 canons on that bass line. Here is a useful and carefully prepared video showing how it works.

ITS HISTORY

There is a prevalent myth that this work had been forgotten until Glenn Gould suddenly revived it in 1955, and made a best selling recording. That is not true. The work was well known in Bach's time. In the 20th century, Wanda Landoska commissioned the building of a harpsichord (an instrument that had gone out of existence), and was the first person to record the “Goldberg Variations” in its entirety in 1933. Her student, the great Bach scholar and performer, Rosalyn Tureck, made many breakthroughs in the study of Bach and made her first recording of the “Goldberg” on the piano in 1953. Musicologist Ralph Kirkpatrick recorded it on a much improved harpsichord the same year.

Many serious musicians were astounded when in 1955, the then 22-year-old Glenn Gould, who had never been outside of Canada, after one performance in NYC, was suddenly lauded by the press as "extraordinary—we know of no other pianist like him." Columbia Records made the unprecedented move of offering him a recording contract, and released a press release extolling his eccentricities as a major selling point. Rosalyn Tureck was not happy over the way Gould copied her discoveries in his 1955 recording of the “Goldberg Variations.” She commented:

“He took a great, great deal from me. Playing his records I hear myself playing, because I was the only one in the world who did these embellishments.”

HARLSICHORD or PIANO?

We recommend you listen to both. Bach wrote it for a two manual (keyboard) harpsichord, and specified which variations should be played on one manual, and which on two. This is because different registers can be employed for the two manuals, thus making them sound like almost two different instruments. For example, the cannon at the ninth in Variation 27 is easier to follow on a harpsichord. Listen to Ralph Kirkpatrick:

The variation 25 ("The Black Pearl") uses a lute stop to accompany the melody:

No piano can do that. On the other hand, the piano has expressive qualities the harpsichord does not.

Tomorrow, we will discuss the marvelous Variation 30.