DAILY DOSE of BEETHOVEN (July 20, 2020)

After Beethoven's death, there are composers who wished to advance the classical tradition and remained true to the compositional method of Bach through Beethoven. That was certainly true for Felix Mendelssohn. We already heard his String Quartet Op. 13, written as a loving tribute to Beethoven after hearing of his death (see May 31st post)—a tribute which quotes three of Beethoven's late string quartets. His dedication to Bach was also lifelong.

In 1828 Mendelssohn organized what was thought to be the first performance of Bach's St. Matthew's Passion in 100 years. Once again, music and science were wed. The great scientist Lejeune Dirichlet was married to Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn's youngest sister Rebecka. All things worked for the Good on the Mendelssohn estate. To quote historian David Shavin:

“When Lejeune Dirichlet, at 23 years of age, worked with Alexander von Humboldt in making microscopic measurements of the motions of a suspended bar-magnet in a specially-built hut in Abraham Mendelssohn’s garden, he could hear, nearby in the garden-house, the Mendelssohn youth movement working through the voicing of J. S. Bach’s “St. Matthew’s Passion.”

Imagine the excitement in the mutual interchange between scientific and artistic thought!

Baron von Swieten had reintroduced Bach to Mozart in 1782. Mendelssohn would now, thirty-six years later, re-introduce Bach to the public. It was a huge success. Bach has been programmed in concerts regularly ever since.

Mendelssohn's crowning personal achievement was his oratorio “Elijah, Op. 70, MWV A 25”, depicting events in the life of the Prophet Elijah as told in the books 1 Kings and 2 Kings of the Old Testament. It was composed to be sung in English and had its world premier in Birmingham England in 1846. Felix was the grandson of Moses Mendelssohn, the Jewish philosopher who is sometimes credited with founding the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment (see May 19th post, the Late Beethoven and the New Synagogue). Even his choice of a last name was a revolution. At the time, Jews were not allowed to have a last name. He was supposed to go by the handle: Moses Dessau, i.e. Moses from the town of Dessau. He said "No! I am not Moses, from Dessau, I am Moses, the son of Mendel", thus Mendelssohn.

Though Felix was brought up without religion, then baptized as a Christian at age 7, he remained proud of his Jewish heritage. When his sponsors in England, including his librettist, wanted to "Christianize" the Oratorio by bringing Saints Paul and Peter on stage near the end, Mendelssohn said, "No, this is about my people."

He found that Europe was in a state of moral decay, and wrote:

“I imagined Elijah as a grand and mighty prophet, of the kind we could really do with today – strong, zealous, and yes, even bad-tempered, angry, and brooding – in contrast to the riff-raff, whether of the court or of the people, and indeed in contrast to almost the whole world – and yet borne aloft as if on the wings of angels.”

If that sounds a bit like a description of Beethoven, we should not be too surprised.

Eljah tells the story of a people being punished (in this case by drought), because of their own moral failings (does it sound familiar?). It opens in D Minor with the brass sounding a four-note theme from Schubert's “Death and the Maiden”. The prophet Elijah follows by intoning, with multiple dissonant tritone intervals:

“As the LORD, God of Israel, liveth, before whom I stand, there shall not be dew nor rain these years, but according to my word.”

Then follows a great fugal overture in D Minor. The theme reminds us of two things:

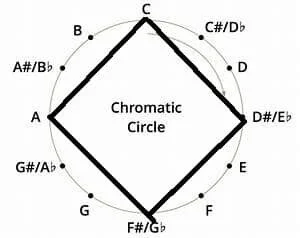

1. The characteristic intervals of the Cminor series, in this case A- Bb and C#-D.

2. The first movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, in the same key, with similar rhythmic motives. (Example 2.)

Listen to the 2 minute long comparison at the end to hear it. First, a passage from Beethoven's 9th. Second, a passage from the overture to Elijah.

Excerpts from Beethoven's Ninth and Mendelssohn Overture: https://soundcloud.com/user-216951281/bach-beethoven-and-beyond-mend

The overture does not end, but rises into an impassioned choral outbreak of "Help Lord. Help Lord! Wilt Thou quite destroy us?" We include a video of the opening, done by the university of Oklahoma.

https://youtu.be/m6T63kJ9cdY

BACH AND HANDEL

Mendelssohn remained true to these two giants. Compare Handel's " Thou shalt Break Them", with Mendelssohn's "Is not his Word Like a Fire?"

"Thou Shalt Break Them"-Handel

https://youtu.be/ONKHjQE02HY

"Is not his Word Like a Fire?"-Mendelssohn.

https://youtu.be/PZAncL9LOnI

Mendelssohn also quotes Bach's "Es ist Vollbracht" from the St. John's Passion. The words are the last spoken by Christ: "It is finished!", while Ia beautiful duet takes place between viola (in this case cello) and alto voice.

https://youtu.be/EuzYE3E0Nfk

Felix' own take on "es ist Vollbracht" is Elijah's own lament, "It is enough". Elijah has given everything for the people of Israel, yet they still demand his head! For Elijah, life has no meaning without a mission!

https://youtu.be/tEkClendR3s

Fortunately an angel draws Elijah back from suicide, and says: "There are 500 people left who have never bent a knee to Baal. Lead them!" The Oratorio ends happily, and powerfully, on the idea "And then shall your light break forth."

https://youtu.be/Y7XARj0FD9E