DAILY DOSE OF BEETHOVEN (September 11, 2020)

Beethoven set many folk songs to music and they are truly a treat. The most striking aspect of these folk song settings is that Beethoven wrote far more of these than any other type of composition, having composed an astounding 179 folk song arrangements, spanning a period of eleven years from 1809 to 1820.

An intriguing feature of these folk song settings is that they are almost entirely in English and consist mainly of Scottish, Welsh and Irish songs. The reason for their existence lies with a Scotsman, George Thomson of Edinburgh (1757-1851). George Thomson, a civil servant by profession, became part of a movement to collect folk songs throughout the British isles in the eighteenth century. Thomson transcribed many melodies on his travels around Great Britain and he also commissioned great poets like Robert Burns and Walter Scott to write new texts for existing folk songs.

Rather than relying on local composers to write the arrangements, Thomson recruited composers with international reputations. He first approached Pleyel, Kozeluch and Haydn, who provided numerous settings. Thomson approached Beethoven in 1803, but did not propose that Beethoven arrange folk song settings for him until 1806, at which time he sent Beethoven a collection of 21 un-texted traditional melodies. Herein lies the beginning of an intriguing collaboration.

Beethoven’s first reply is dated November 1, 1806. It discusses various proposals and shows that Beethoven knew full well that ‘Mr. Haydn was given a British pound for each air’. Ultimately, Thomson paid Beethoven four ducat per song, twice what Haydn was paid initially. However, it was 1809, that Beethoven finally agreed to collaborate, with the first batch of settings – 53 in all – completed in July 1810. Beethoven sent three copies but none reached Thomson until about July 1812, due to the chaos of the Napoleonic war. When it finally did, it appears to have been sent via Malta! Beethoven later sent his works by way of Paris. But the only way to successfully send these consignments was to enlist the aid of smugglers.

Beethoven described his settings as compositions, which suggests that he took the commissions seriously. Responding to one of Thomson’s many requests that he simplify his accompaniments, Beethoven placed the settings implicitly on a level with his other works, when he testily declared:

“I am not accustomed to retouching my compositions; I have never done so, certain of the truth that any partial change alters the character of the composition. I am sorry that you are the loser, but you cannot blame me, since it was up to you to make me better acquainted with the taste of your country and the little facility of your performers.”

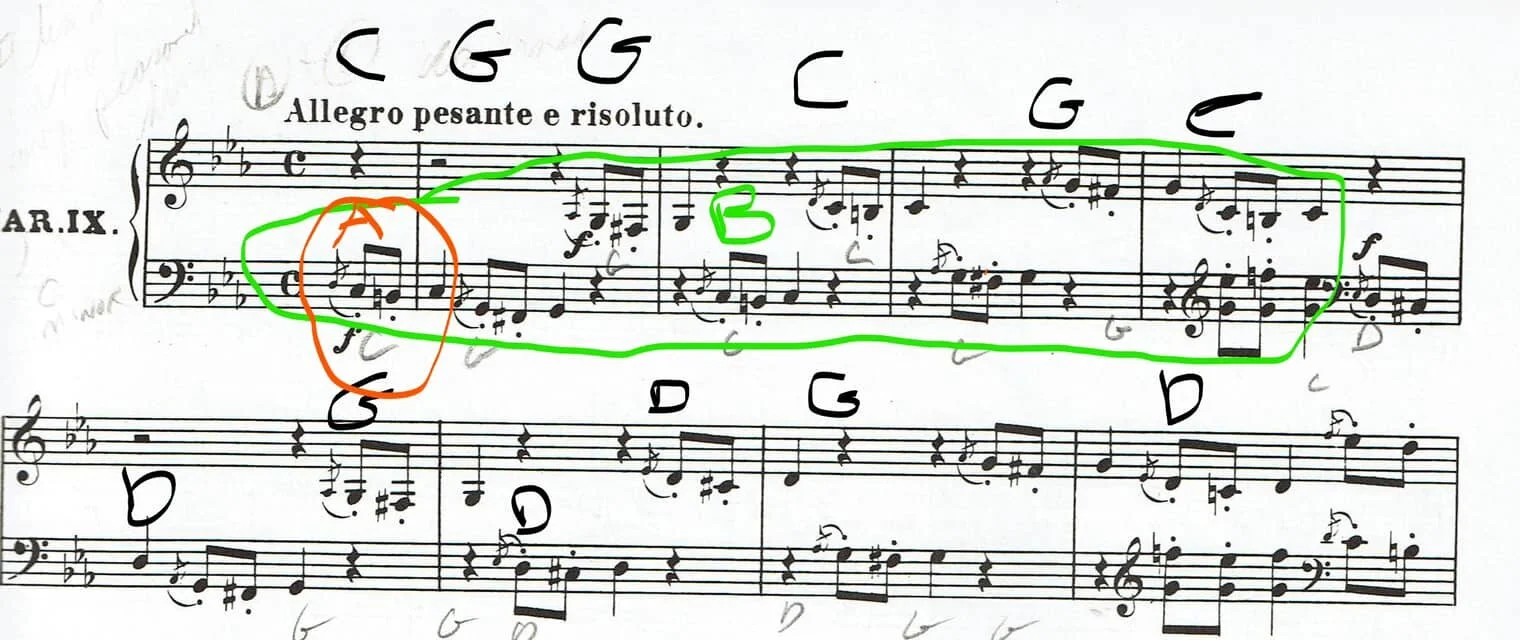

The 25 Scottish Songs (or “Twenty-five Scottish songs: for voice, mixed chorus, violin, violoncello and piano, Op.108”) was published in London and Edinburgh in 1818, and in Berlin in 1822. It is the only set among Beethoven's folksong arrangements to be assigned an opus number.

Beethoven’s arrangements for these folk songs are ingenious. The violin and cello parts are designed to be optional, but they are no simple reproduction of the piano part. They are sufficiently independent so as to add interest when used, while detracting nothing when omitted. Another is that the folk settings required Beethoven to work with modal harmonizations in a classical context, sometimes using drone basses which are suggestive of a bagpipe, yielding some strikingly beautiful results. These settings display tremendous energy in the faster settings and haunting expressiveness in the slower ones, combining rich textures and innovative harmonization with delightful variety.

Here’s are the songs:

1-5 https://youtu.be/wsgYUYB-jqM

6-10 https://youtu.be/xSjsYP9DKGg

11-15 https://youtu.be/CK-jkpe08Gc

16-19 https://youtu.be/9qQHWQ8zmTU

23-25 https://youtu.be/MUPbtySnxmg