DAILY DOSE of BEETHOVEN (October 6, 2020)

Brahms' patriotism is well known. He had a portrait of Bismarck on his living room wall, and remarked that the two greatest events of his life were the publication of the complete works of Bach, and the unification of Gemany. His sense of humor is not as well known, but it is linked to his irrascibility when confronted with Dummkopfs (stupidity, or a blockhead).

In 1880, the University of Breslau awarded Brahms an honorary Doctor of Philosophy. Brahms had little use for such academic titles, and was content to write a thank-you note. The university however, expected nothing less than a new composition, written especially for the occasion.

The conductor Bernard Scholz, who had recommended the award, wrote somewhat arrogantly to Brahms: "Compose a fine symphony for us, but well orchestrated, old boy, not too uniformly thick!"

Can you imagine the audacity to first demand a symphonic work from Brahms, and then tell him how to compose it? Brahms mistrusted academics, who sometimes belittled him, and gossiped about his lack of overall education. For Brahms, a degree in music from a University was just the starting point. It meant only that now you were ready to start discovering music, in the way he had done.

He went ahead with an orchestral work, but not as planned! Brahms responded to Scholz' demand that the orchestration be "not too thick", by assembling a huge orchestra of piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, one tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

The stiff university leaders probably wished him to employ some sort of stultified graduation song as its basis. Instead Brahms conducted the work for a special academic convocation, which is usually a serious matter. Brahms wrote that he had created a "very boisterous potpourri of student drinking songs, à la Suppé".

Brahms created a sort of modified "Quodlibet", after the tradition of Bach, and incorporated four student songs. They were all drinking songs, but some were also very political. Some of the university staff were aghast, while some might have been secretly pleased. Although German unification had been proclaimed in 1871, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, it was still a hot issue when Brahms composed this work in 1880.

For our listener/reader to enjoy this at a higher level, we provide all 4 songs. When you get to know them, the final composition-the overture-will become 1,000 times richer, including its humor.

We recommend singing along with the verses provided, at least until you are sure you know each song!

Song 1: Fuchslied (Fox Song), which was used while hazing freshmen. It is similar to our English "Farmer in the Dell", and "A Hunting we Will Go”: https://youtu.be/2CG-y8FTa8E

1. (Studenten)

Was kommt dort von der höh'?

Was kommt dort von der höh'?

Was kommt dort von der ledern' höh'?

Ça, ça, ledern' höh',

Was kommt dort von der höh'?

(Students)

[What comes there from on yonder?

What comes there from on yonder?

What comes there from on bloody yonder?

Sa, sa, bloody yonder,

What comes there from on yonder?]

2. Es ist der Fuchsmajor,

Es ist der Fuchsmajor,

Es ist der ledern' Fuchsmajor,

Ça, ça, Fuchsmajor,

Es ist der Fuchsmajor.

[It is the Foxmajor,

It is the Foxmajor,

It is the bloody Foxmajor,

Sa, sa, Foxmajor,

It is the Foxmajor.]

3. Was bringt der Fuchsmajor?

Was bringt der Fuchsmajor?

Was bringt der ledern' Fuchsmajor?

Ça, ça, Fuchsmajor,

Was bringt der Fuchsmajor?

[What brings the Foxmajor?

What brings the Foxmajor?

What brings the bloody Foxmajor?

Sa, sa, Foxmajor,

What brings the Foxmajor?]

4. Er bringt uns seine füchs',

Er bringt uns seine füchs',

Er bringt uns seine ledern' füchs',

Ça, ça, ledern' füchs',

Er bringt uns seine füchs'.

[He brings us his foxes,

He brings us his foxes,

He brings us his bloody foxes,

Sa, sa, bloody foxes,

He brings us his foxes.]

5. (Fuchs)

Ihr Diener, meine herr'n,

Ihr Diener, meine herr'n,

Ihr Diener, meine hohe herr'n,

Ça, ça, hohe herr'n,

Ihr Diener, meine herr'n!

(Foxes)

[At your service my gentlemen,

At your service my gentlemen,

At your service, my noble gentlemen,

Sa, sa, gentlemen,

At your service my gentlemen.]

6. (Foxmajor)

Ich bring' euch meine füchs',

Ich bring' euch meine füchs',

Ich bring' euch meine ledern' füchs',

Ça, ça, ledern' füchs',

Ich bring' euch meine füchs'.

(Foxmajor)

[I bring you my foxes,

I bring you my foxes,

I bring you my bloody foxes,

Sa, sa, bloody foxes,

I bring you my foxes. ]

7. (Studenten)

So wird der fink ein fuchs,

So wird der fink ein fuchs,

So wird der ledern fink ein fuchs,

Ça, ça, fink ein fuchs,

So wird der fink ein fuchs.

(Students)

[Thus, the finch becomes a fox,

Thus the finch becomes a fox,

Thus, the bloody finch becomes a fox,

Sa, sa, finch a fox,

Thus, the finch becomes a fox.]

Song 2: Wir haben gebauet Ein stattliches Haus (We have built a stately house): https://youtu.be/U5wKYbSz3oM

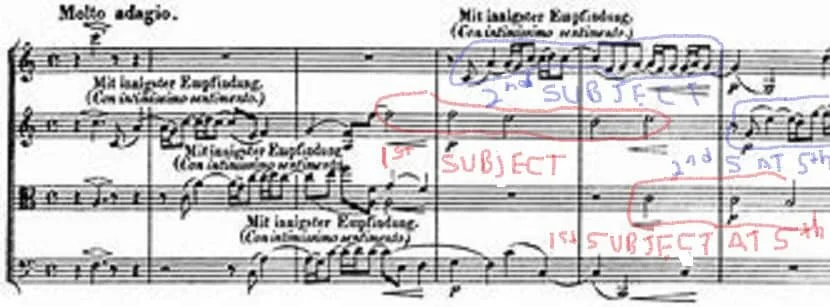

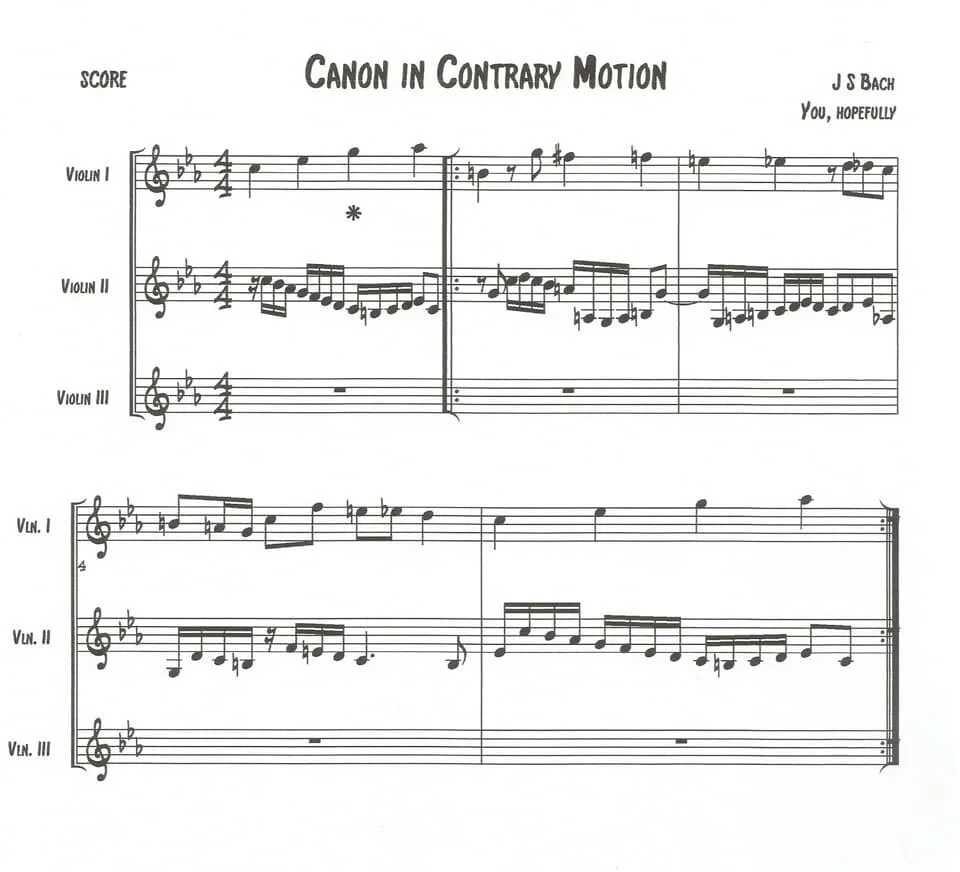

This drinking song was also a patriotic song, written 60 years earlier in 1820, by a leader of the student's union, after it was shut down by the dictatorial Carlsbad decrees. The cartoon (see picture below), is from 1819, and shows members of a Thinkers' Society wearing muzzles. The stately house is Germany, and it mentions the colors of the flag: black, red, and gold. Sixty years later, in 1880, when Brahms composed the Overture, it was still controversial.

Text and Translation:

1. Wir hatten gebauet

Ein stattliches Haus

Und drin auf Gott vertrauet

Trotz Wetter, Sturm und Graus.

[We had built

A stately house

And trusted in God therein

Despite tempest, storm and horror.]

2. Wir lebten so traulich,

So innig, so frei,

Den Schlechten ward es graulich,

Wir lebten gar zu treu.

[We lived so cozily,

So devotedly, so free,

To the wicked it was abhorrent,

We lived far too faithfully.]

3. Sie lugten, sie suchten

Nach Trug und Verrat,

Verleumdeten, verfluchten

Die junge, grüne Saat.

[They peered, they looked

For deceit and treachery,

Slandered, cursed

The young, green seed.]

4. Was Gott in uns legte,

Die Welt hat's veracht't,

Die Einigkeit erregte

Bei Guten selbst Verdacht.

[What God put inside us,

The world has despised.

This unity stirred suspicion

Even among good people.]

5. Man schalt es Verbrechen,

Man täuschte sich sehr;

Die Form kann man zerbrechen,

Die Liebe nimmermehr.

[People reviled it as crime,

They deluded themselves badly;

They can shatter the form,

But never the love.]

6. Die Form ist zerbrochen,

Von außen herein,

Doch was man drin gerochen,

War eitel Dunst und Schein.

[The form is shattered,

From out to within,

But they smelled inside it

Sheer haze and appearance.]

7. Das Band ist zerschnitten,

War schwarz, rot und gold,

Und Gott hat es gelitten,

Wer weiß, was er gewollt.

[The riband is cut to pieces,

T'was black, red and gold,

And God allowed it,

Who knows what He wanted.]

8. Das Haus mag zerfallen.

Was hat's dann für Not?

Der Geist lebt in uns allen,

Und unsre Burg ist Gott!

[The house may collapse.

Would it matter?

The spirit lives within us all,

And our fortress is God!]

Song 3: Alles schweige! Jeder neige.

This is also a patriotic song, part of a ceremont called “Landesvater”. It originally pledged loyalty to Emperor Joseph II, who supported Mozart. Later, it referred to loyalty to Germany.

Brahms uses only the section that starts "Hört, ich sing' das Lied der Lieder”' , or 'Listen I sing the song of songs”: https://youtu.be/TA1ru4Z2ZCU?list=RDTA1ru4Z2ZCU

1. Alles schweige! Jeder neige

ernsten Tönen nun sein Ohr!

Hört, ich sing' das Lied der Lieder,

hört es, meine deutschen Brüder!

Hall es wider, froher Chor!

[Be silent! Everyone tend

serious tones now his ear!

Listen, I sing the song of songs

hear it, my German brothers!

Echo it, happy chorus!]

2. Deutschlands Söhne laut ertöne

euer Vaterlandsgesang!

Vaterland! Du Land des Ruhmes,

weih'n zu deines Heiligtumes

Hütern uns und unser Schwert!]

[2. Germany's sons sound out loud

your fatherland song!

Fatherland! You land of glory

consecrate to your sanctuary

Guard us and our sword!]

Finally, if university had wanted a 'comercium', or graduation song, they finally got it, but the well known “Gaudeamus igitur”, is also a ribald drinking song. Brahms turns it into a powerful ending for his overture. The words are included in the video: https://youtu.be/aLUKfU2AOBY

Once you know all four songs, you can have fun appreciating how Brahms weaved these songs into a theme of his own making, and totally upset the "serious" atmosphere he had been required to create.

Here is the full Academic Festival Overture, presented, appropriately, by a student orchestra.

https://youtu.be/O66M8p8AwAo

NOTE: This post was originally created on August 17, 2020. It has been rewritten to present a more complete story. Please enjoy!